IN SEARCH OF PORCELAIN

In Search of Porcelain is an exploration of the potential and obstacles in the utilisation of Icelandic minerals to make porcelain. The idea for the project was sparked by the history of porcelain, the impact of this remarkable substance on our culture, and the way it impelled constant experimentation and technical advances.

Behind the substances we take for granted in our daily lives, lies a centuries-long process of evolution – a progression in humanity’s relationship with nature, driven by the indefatigable curiosity of mankind, in the constant quest to transform previously unutilised aspects of nature.

Our search for porcelain is propelled by that same curiosity and desire for transformation – as we remove substances from their natural setting and give them a new role and a new form.

ABOUT PORCELAIN

Porcelain is a composite material, a ceramic of vitreous, white mass, made of several different minerals, fired at high temperatures, around 1250 – 1400°C. A bit different from the original Chinese mix the European porcelain mixture is usually made from three minerals: kaolin clay, quartz and alkali feldspar. These minerals are abundant in many places where erosion has washed piles of kaolin clay and quartz sand out of ancient silicic continental crust. The continental crust is also rich of alkali feldspar, and before it used to be mined out of macrocrystalline granite called pegmatite, which was used for quartz mining as well. In areas where pure quartz and alkali feldspar was unavailable other minerals were used and accordingly there exist various porcelain mixtures, with different properties, colours, textures and applications.

Porcelain was first developed and produced in China around 1500 – 2000 years ago, and for a long while China was the sole producer. It arrived in Europe late 13th century and soon became very popular. Still Europeans didn’t manage to produce real high-fired porcelain until the dawn of the 18th century, more than 1000 years after the Chinese had mastered the skill.

Porcelain production in Europe started in Meissen in Saxony but soon spread to other European countries, like France, England and Denmark. In the late 18th century, the establishment of the Royal Danish Porcelain Factory (later known as Royal Copenhagen) sparked a Danish interest in Icelandic porcelain clay, known from a remote locality named Bleikjuholt in Mókollsdalur Valley in Strandir, northwest Iceland. The Danes studied the clay briefly but eventually didn’t use it for their porcelain production, as the mining would have been very expensive, and they’d already found usable porcelain clay in Bornholm.

Experiments with clay in Iceland didn’t start until the 20th century so they are very recent by comparison with most cultures, where clay has been utilised for thousands of years. But when porcelain manufacture began in Denmark in the late 18th century, Iceland came close to having a part to play in the rapid industrial development taking place in Europe – but that came to nothing.

ICELAND AND PORCELAIN

Iceland is young on a geological timescale. The geological processes found on the continents are not encountered in Iceland, not only because of Iceland’s age, but also because of the bedrock composition and Iceland’s very distinctive geological setting on top of the Mid-Atlantic ridge. Most cultures on Earth have therefore originated and developed in landscapes very different from Iceland.

Clay is rare in Iceland and most of it is either glacial river run-off (not true clays in the mineralogical sense) or of geothermal origin. Apart from limited quantity the clay is also mostly impure, mixed with rock fragments (the glacial clays) or minerals incompatible with ceramic making such as sulphur and gypsum (the geothermal clays). The chemical composition of Iceland’s bedrock, which is mainly basalt, is a large factor in preventing mature clays from forming. The kaolin (often known as China clay) needed for porcelain is made up of silica and a blend of sodium and potassium (combined in alkali feldspars). The alkali feldspars are very limited in Iceland resulting in most Icelandic clays being unfit for ceramic making. Modern ceramicware made from Icelandic clays is almost only earthenware. Although it would be possible to isolate the primary raw materials for porcelain and purify them with advanced mechanical and chemical methods, it is hardly feasible due to cost and the small amount of raw materials

Here, the special geology of the country has forced us to explore other paths that have not been studied well before in Iceland. To make Icelandic stoneware that resembles true porcelain one would have to compromise somewhat in combining the raw materials. The alternative to using pure quartz and alkali feldspars is using alkaline rocks such as rhyolite and granite which can be found in some quantity in Iceland. They contain both required minerals but unfortunately other minerals as well, so they are not nearly as pure. For the best results we chose to incorporate granitic rock from Slaufrudalur in the south-east of Iceland.

For the plastic clay needed for our mixture of porcelain material there is a unique place in the north-west of Iceland, called Bleikjuholt (“bleikja” hinting at its colour of pink or yellow hue). Here rock dissolving processes of an ancient high-temperature geothermal area have resulted in the build-up of an almost completely pure kaolin clay. This is the only such place found in the whole country. Mixing material from these two places, Slaufrudalur and Bleikjuholt, gave us our clay mixture resulting after high firing in a yellowish grey near-porcelain material.

BLEIKJUHOLT

In a little valley in Mókollsdalur á Ströndum, north-west Iceland, lies the unique Bleikjuholt hillock, known as a location for kaolin or porcelain clay in Iceland. The name of the hillock is a reference to the clay itself, which is white or pale pink in colour and called "bleikja", meaning "pink". Through the centuries it was considered by many to be a healing balm. The clay patch is connected to an ancient geothermal heat in the area, and there is a weather-worn dyke around Bleikjuholt that once drew geothermal water from deep underground up towards the surface.

The area has, without doubt, been known of since ancient times and it is first mentioned in Ferðabók Eggerts og Bjarna in 1772. Between 1775 and 1785 the Danes studied the clay with the idea of using this domestic raw material for porcelain production, which had just begun at the royal porcelain factory in Copenhagen. A significant amount was sent to Denmark by ship, but it disappeared at sea, and so none of the clay was used in this process.

There was not much activity at the hillock for the next 150 years, but the British did do some research there around 1940, removing roughly 50 tons of kaolin by horse for industrial use. But that was the extent of its exploitation, and so Bleikjuholt still sits, pristine white, in the small alley. It is a walk of a few hours among the mounds and hillocks to get to this small hill, and therefore there is considerable difficulty to access the kaolin although over the years individual ceramicists have scrambled there to get hold of the material.

SLAUFRUDALUR

Midst the greyish basaltic mountains of Iceland lies the odd valley of Slaufrudalur, full of white granitic rocks in contrast with the surrounding dark bedrock. The rocks are of similar age as Bleikjuholt, around 6-7 million years old, but on the other side of Iceland, in the south-east. The rocks were originally emplaced deep in the earth crust as a large pluton. Later they surfaced after many erosional cycles of ice age glaciers chiselling away the bedrock lying above and creating the landscape we see today.

Icelandic granitic rocks have had no practical or economic value throughout the nation’s history, but as granite is mostly made up of quartz and alkali feldspars, they are very suitable for our project and come closest to obtaining pure quartz and feldspar crystals. The white rocks are easy to collect as the ring road around Iceland passes in front of the valley. To get the purest and the least metamorphosised rocks we hike along the river flowing at the bottom and collect boulders from the bottom of the valley. Perhaps we could find even better samples higher up, but the cliffs are impossible to scale.

METHODS

We collected samples from all over Iceland, apart only from the far east. Some we could access on car but the most important materials, especially the kaolin from Bleikjuholt, we had to hike over long distances to collect and carry on our backs back.

After collecting we started processing the samples. We tried to manipulate the materials as little as possible, preferably only with methods already available in the 18th century but with no advanced mechanical or chemical washing. The clays were washed with water to get rid of sulphur and salts while the rocks were crushed into fine dust in small ball mills. As the granite has small quantity of iron-bearing minerals with magnetic properties we tried to clean the ground material with magnets.

These processes resulted in two main ingredients for our porcelain making experiments: kaolin from Bleikjuholt and ground granite from Slaufrudalur. To realise their potentials, we further explored these two components with both chemical and x-ray mineral analysis. Later, after ceramic firing, we also made thin sections to look at the change in mineral composition during the firing process. Chemical analysis showed that the kaolin was very pure compared to well-known kaolin mines in Europe and America, with only slightly higher titanium content, explained by the geothermal origin. The granite after iron cleaning with magnets was a good substitute for pure quartz and feldspar. The porcelain mixture was still a bit impure with titanium and iron which would only have been possible to purify further with advanced techniques. As a result, the porcelain after second fire was a bit off-white, yellowish and greyish explained by the additional chemicals.

RESULTS

Through interdisciplinary research between a designer, a ceramicist and a geologist we have shown that is indeed possible to make hard high-fired stoneware out of Icelandic earth materials, close to porcelain in both composition and look. Because of the off-white colour most would probably not label or classify it as a real porcelain but that is of course up for debate. We like to define it as a raw stoneware native to Iceland, resembling the rough nature and the basaltic soil that dominates Icelandic nature.

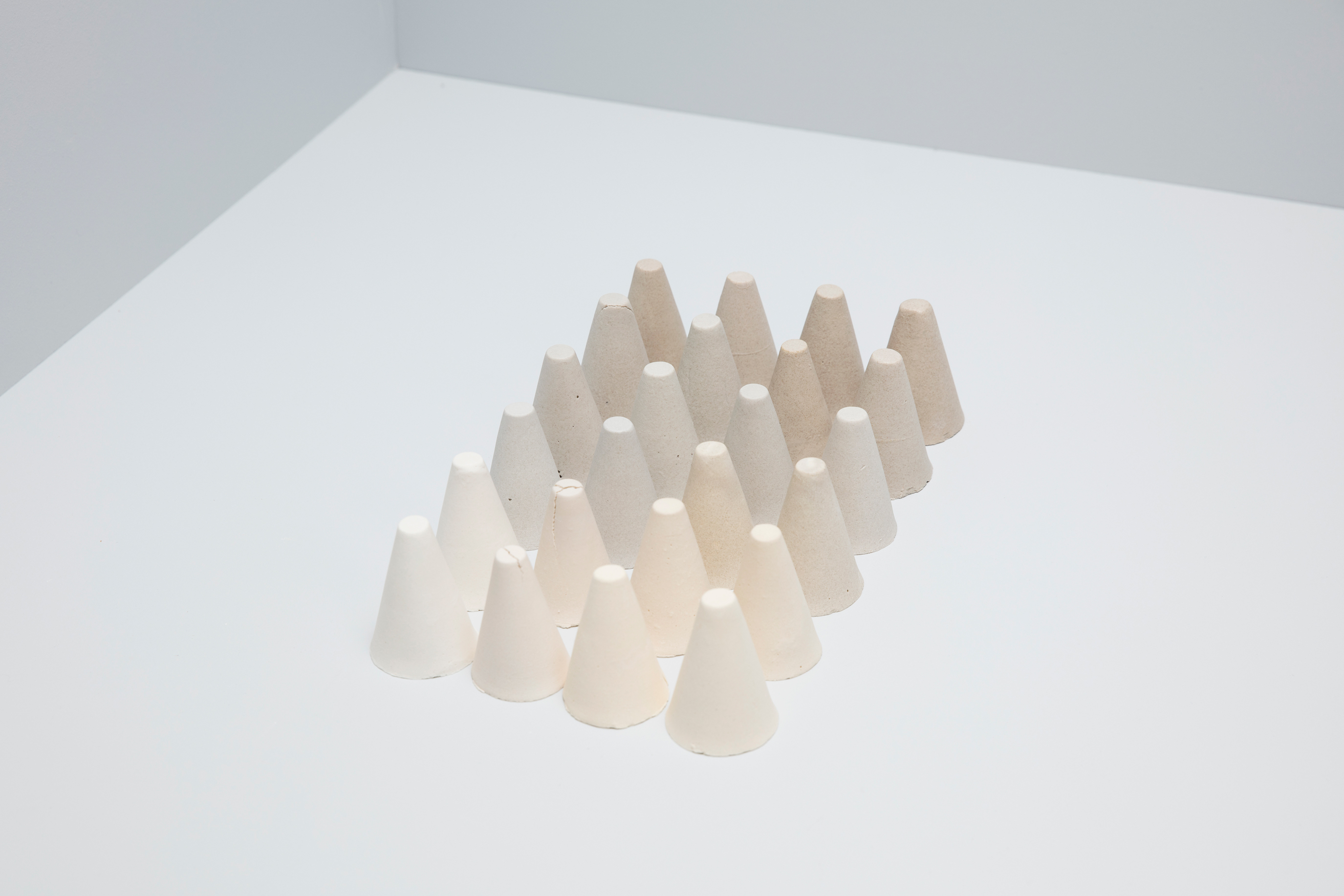

In 2020 we made a series of small objects out of this Icelandic “porcelain” that highlight the delicacy, rarity and origin of the material. The project In Search of Porcelain was never intended to be a short-term project and is still in development. In that sense it is like the material itself that matures with time, ceramic clays often being stored for years or even generations. Hopefully the project will inspire more research on Icelandic earth materials.

THE TEAM

Brynhildur Pálsdóttir (brynhildurpalsdottir.is) works as a designer in Reykjavik and has participated and directed many diverse projects, addressing her local environment while keeping interdisciplinary approach in collaboration with different professionals. As a result, local materials and culture are the focus of attention in her work. Brynhildur has lectured both at The Reykjavik School of Visual Arts and the Iceland Academy of the Arts.

Ólöf Erla Bjarnadóttir (oloferlakeramik.is) is a ceramicist and a former head of the Ceramic Department at The Reykjavik School of Visual Arts. Ólöf has for decades run her own ceramic studio, where she has worked porcelain, throwing, hand-building and casting it. During that time, she has developed her own methods and ideas, relating for instance to ceramic glazes and coloured porcelain bodies. Ólöf's work are experimental and characterised by constant search for new possibilities in manipulating the material.

Snæbjörn Guðmundsson , geologist at the Icelandic Museum of Natural History, has since 2009 focused on geoscience communication for the public, especially for children, where he develops different ideas related to nature interpretation and communication. Snæbjörn was a lecturer of mineralogy at the University of Iceland’s Faculty of Earth Sciences and lectures at University of Iceland Centre for Continuing Education. Snæbjörn is the author of Exploring Iceland's Geology (2015, English translation 2016), a survey for general readers of 100 geological sites in Iceland.